Each day I set out materials and plan experiences for

children of many different ages. There are always many variables at work during

any given visit, and I never know exactly how things will go. Sometimes I am

frustrated if the set-up does not prove as inspiring as I had hoped, or if

children need a lot of help and reminders to respect the materials that are

available. I start to feel like a failure. However, even in those

moments, the children’s actions and reactions hold the seeds for a way out of

those feelings, and into more successful set-ups the next time.

Throughout the autumn, each session in the Studio is an

opportunity for children from a classroom to familiarize themselves with a

particular material, as well as the Studio space itself. For young toddlers,

most of this experience lies in “messing about,” where materials are set out

with minimal guidance or instruction. Preschoolers and older toddlers will

experience this, as well, but may move on to learning particular techniques

that will help them to use the material with more finesse.

For example, Preschool Two moved from

open experimentation with clay on tables and on the

floor,

to learning about scoring and adding slip,

to opening, pinching, and attaching pieces of clay

using the score and slip technique,

to creating sculptures modeled on hydrangeas,

black-eyed Susans, and asters set out on the table.

This process required learning from me, my fellow

teachers, and the children. Each time a small group worked in the Studio, I

learned something about their thinking and understanding of the clay. I learned

what aspects of the day’s work they found challenging and what parts they were

able to connect to what they had done before. This new knowledge helped me

decide what changes I should make when I worked with this group or others.

For example, we practiced the method of scratching and

wetting the surface of the clay to attach pieces to each other. Since we moved

right into this method when we sat down, the children began to join pieces of

clay without really shaping them. They weren’t very invested in their work, and

they didn’t notice the shape and potential “being” of their clay. I realized

that for them to gain the practice and skills I was hoping for, we would have

to approach the problem a little differently.

For the following groups, we started not with joining

pieces, but with making shapes from the clay. Children were very confident in

creating long “snake” shapes, and balls, and soon they had many pieces to

choose from. Now was the time to work in the joining process. The children

already had their pieces shaped, so joining them together became an opportunity

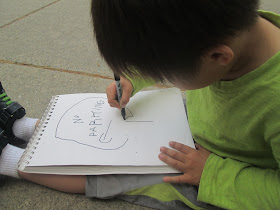

to form something new. The experience this time around was much richer. Nava and Everett both began to experiment in forming

symbols from their clay pieces. M. made several snakes that she lined up “like a

train.” Phineas joined his snake shapes into a single long path

that curled around his board.

Encouraged by this, I incorporated this successful process into the following week, where children spent time opening a large piece of clay together, creating a communal base that they could then add pieces onto using the same techniques we had been practicing.

The creations that children came up with were amazing!

Their blocks of clay transformed into sidewalks, then houses, then waterparks!

They began to attach their clay in more careful and intricate ways, creating

bridges and waterspouts. One group – featuring Justin, Phineas, and F. –

decided very early on that they wanted to create some sort of building

together.

“I’m making sewers,” Justin said as he dug holes near

the bottom of the mound, “I’m making a place to catch the rain so the house

doesn’t get ruined.”

Phineas began to attach a long snake near the top,

“This is the thing that makes the lightning so it doesn’t hurt the house.”

When we reached our session of recreating flowers in

clay – our chance to put all of our knowledge of this material together as we

examined these specimens of the natural world – I could see the children’s

previous experiences come into play. At first they made the parts of their

flower – sometimes the stem, sometimes the petals or leaves – before thinking

about how they would join them together. Luke, who was making a black-eyed Susan, rolled a

single long snake that he broke into smaller pieces for his petals. Phineas worked to shape his leaf for the same plant so

that it “bends” just like the one on the real plant.

Some children, like Nava, E., and Luke, sought to

make their flowers stand up, while others lay them flat on their boards – each

technique bringing its own unique challenges. They carefully went through the steps – score, wet,

push together, and smooth – for each piece that they joined, clearly invested

in making something that would hold together.

Some children, like Nava, E., and Luke, sought to

make their flowers stand up, while others lay them flat on their boards – each

technique bringing its own unique challenges. They carefully went through the steps – score, wet,

push together, and smooth – for each piece that they joined, clearly invested

in making something that would hold together.

Many of the children began with the black-eyed Susan as

their muse – the flower they declared to be the “easiest” to make. One

particularly satisfying moment for me as a teacher was when Everett and Phineas

had each finished this flower and decided to “try” to make another – the

hydrangea – with its small, round petals. Everett even went on to do the

“hardest one,” the aster, complete with “all of those spiky leaves.”

Thinking back to our first attempts at attaching clay

pieces to each other, I was grateful for what the children had taught me in

teaching them. Working alongside them, I had learned to slow down, think first

about shaping the clay, then about how it should fit together, before moving on

to the actually joining process. The children’s growing confidence in their

work was a testimony to their own learning, as well as my own.

Each class is broken into many groups and each group

comes for the same general experience in the Studio. But I know I would not be

doing my job as a teacher if I offered each group exactly the same experience.

I am always so grateful to the first group that comes, because they help me to

see what works and what doesn’t about how I have planned, arranged, and

introduced the day’s session.

Sometimes the smallest tweak in a set-up can make it more inviting, and the slightest re-structuring of a material’s presentation can help children to embark on a new relationship with it. Those moments of so-called failure can often be the best moments for learning, because they force you to think even more deeply about your own reactions and the reactions of the children you observed, just as the tumbling down of a child’s clay structure invites them to consider new and better ways to build it. Art educator Jessica Hoffman Davis believes that one of the best arguments for keeping arts in our schools is that they offer “the chance to have daring, edgy, generating, and important encounters with failure… For artists, mistakes open doors for their work.” I would say that perhaps the same goes for teaching. Teaching is not (and should not be) about getting everything right the first time. It is about the “generative” process of learning from and growing through our failures, and seeing them for the amazing teachers they are.

"In Defense of Failure" by Jessica Hoffman Davis, EdWeek, October 8, 2003.